A Brief Guide to the Latest IPCC Report on Climate Change

Updated November 29, 2023 by Neil Simpson

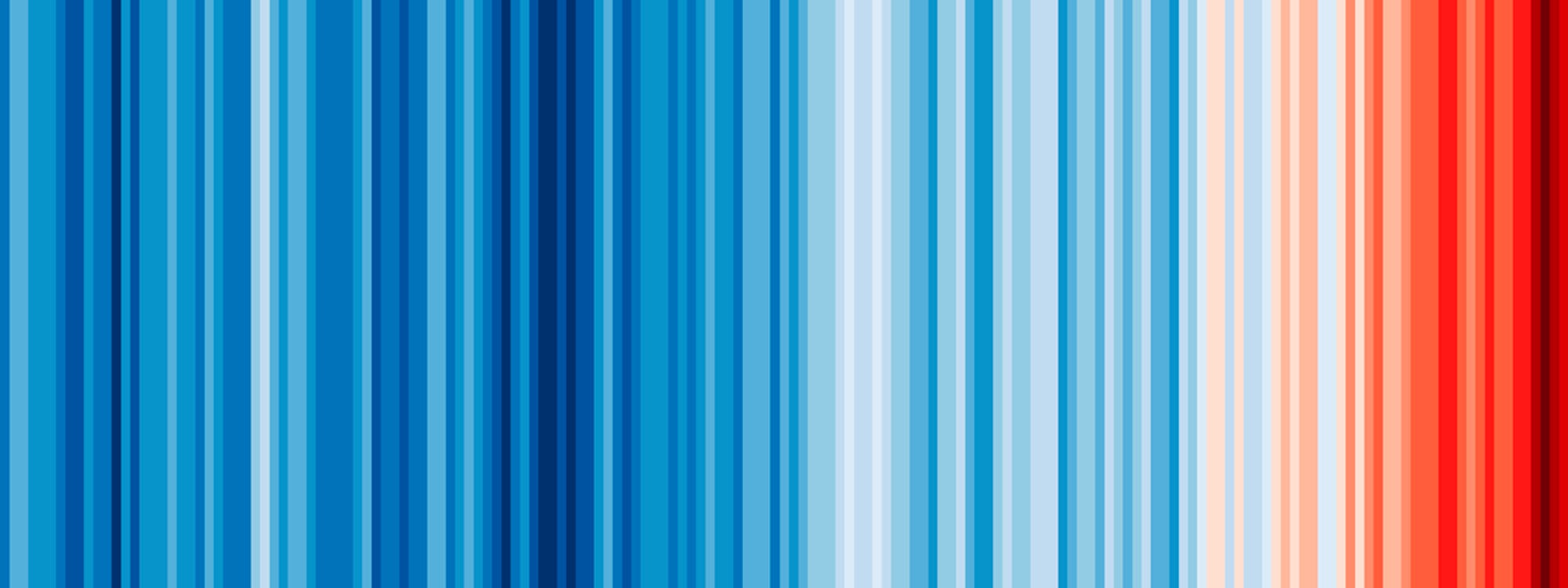

Global temperatures from 1901-2020; each stripe represents the temperature averaged over a year. By Professor Ed Hawkins (University of Reading) [source]

The sixth IPCC report is headline news, especially as it arrives amid a sudden proliferation of wildfires and floods around the globe. But the report’s detailed and complicated nature has created a somewhat bewildering media blitz. This mini-guide breaks down the new report into digestible essentials and describes how it relates to banking.

The IPCC story

IPCC stands for Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which the United Nations Environment Programme and World Meteorological Organization created in 1988. The IPCC’s job is to collate the world’s total scientific knowledge on climate change in one place.

The IPCC gathers hundreds of scientists, who analyse more than 14,000 publications on climate change. The report clocks in at more than 3000 pages and represents a colossal amount of work – that’s why the IPCC has published just six reports since 1988, roughly once every six years. The latest was released on 9th August 2021.

As well as the full, lengthy report, there's the shorter Summary for Policymakers that every government in the world reviews prior to its publication. There must be total agreement upon every line in this summary. If total agreement isn't possible, the scientists have the final say for the sake of factual accuracy.

It is worth noting that this is only part one of the latest report, which is concerned with the physical science of climate change. Parts two and three, which describe how to mitigate climate change and adapt to the changes that are no longer avoidable, are due in 2022.

What does the sixth IPCC report say about climate change?

The IPCC was never able to say with certainty that human activity is causing climate change. Now, for the first time, it has:

‘It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere [ice-covered regions] and biosphere have occurred.’ p.6; Summary for Policy Makers

The report concludes that we are almost certainly heading for at least 1.5°C of global warming since the Industrial Revolution, before the end of this century:

‘Global warming of 1.5°C relative to 1850-1900 would be exceeded during the 21st century under the intermediate, high and very high scenarios considered in this report.’ p.19

1.5°C is repeatedly talked about because it is key to the United Nation’s Paris Agreement: In 2015, every country in the world united in Paris to say that global warming must not exceed 2°C, but ‘preferably’ not 1.5°C. The latest IPCC report, however, says that it is ‘more likely than not’ that we will exceed 1.5°C, even if the world immediately creates a ‘very low greenhouse gas emissions scenario.’

Rising temperatures result in a range of catastrophic outcomes for all of us, such as rising sea levels. The report explains that there is now nothing we can do about that particular outcome, because there is so much heat trapped in the sea:

‘In the longer term, sea level is committed to rise for centuries to millennia due to continuing deep ocean warming and ice sheet melt, and will remain elevated for thousands of years (high confidence).’ p.28

The report explains that climate change will ‘become larger in direct relation to increasing global warming’. This means that, even though containing global warming to 1.5°C looks very unlikely, 1.6°C of warming would still be preferable to 1.7°C, and so on. The higher the temperature, the greater the heatwaves, precipitation, droughts, and cyclones will become.

The first part of the sixth IPCC report contains massive amounts of information, but the most concerning facts are:

- It is now beyond doubt that greenhouse gas emissions resulting from human activity are causing global warming, which is changing the climate

- It is almost certain that global warming will exceed 1.5°C during this century

- Sea levels are going to rise for thousands of years

What needs to happen?

Human-generated greenhouse gas emissions must decline dramatically and immediately. That’s because these gases, which include carbon dioxide and methane, become trapped in Earth’s atmosphere. When energy rays (such as heat energy rising from the land and sea) meet these gases, they bounce away in all directions. Rays that bounce back down cause the temperature of Earth’s surface and lower atmosphere to rise. These temperatures will rise as the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increase.

A major source of carbon dioxide is the burning of fossil fuels: humans are moving carbon from the ground to the air, where it is accumulating in ever-greater concentrations.

Coal mining; TripodStories- AB - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0 [source]

According to the Rainforest Action Network, the world’s 60 largest commercial and investment banks provided $3.8 trillion USD in financing for the fossil fuels industry between 2016 and 2020. This activity is growing, not shrinking.

We are reaching a crucial point in human history, with the release of the IPCC’s sixth report coming just before COP26 in November, when world leaders will meet and negotiate carbon emission reductions in honour of the Paris Agreement (read our COP26 article here). These negotiations must result in radical commitments and action, which is more likely to happen with public pressure.

What can you do to help?

One thing you could do is spread the word about Bank.Green and the urgent need to move as much money as possible away from fossil fuels – talk to your bank, your friends, and your family. Visit our Take Action hub for help.

We appreciate that IPCC reports, COPs, Paris Agreements, and 1.5°C thresholds are confusing and overwhelming – especially when you’re telling Great Aunt Judith. So, we’ve compiled some straightforward talking points that should help.

- The basics - The global scientific consensus, backed up by data collected by thousands of experts working across the world, is that deep cuts in CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions must begin immediately. These emissions are heating the planet and changing the climate, so the longer we delay, the more droughts, wildfires, heatwaves, cyclones, mass migration, and civil unrest we will experience.

- The banking link - The world’s biggest banks continue to finance the fossil fuels industry, providing trillions of dollars for expansion. The IPCC report makes it extremely clear that the burning of fossil fuels cannot continue if we wish to minimize climate change and the potentially catastrophic impacts for humans and biodiversity. Telling your current bank that you’re seriously considering moving your money elsewhere is one of the most powerful things one can do. Banks rely on our money, so they will change if enough of us make it clear that they have no other choice.

For further inspiration, ideas, and tips on talking to your bank about fossil fuels financing, visit our Take Action pages.

Download the IPCC’s Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, Summary for Policymakers

Start to Bank Green Today

Banks live and die on their reputations. Mass movements of money to fossil-free competitors puts those reputations at grave risk. By moving your money to a sustainable financial institution, you will:

Send a message to your bank that it must defund fossil fuels

Join a fast-growing movement of consumers standing up for their future

Take a critical climate action with profound effects